Here we will explore the use of religion in the earlier years of comic books. This will work to give us a good idea of how religion played a part in the creation of the personalities of some of comic books' most iconic heroes and villains. The following information was obtained from S. Brent Plate

Every Where You Look

Scratch the surface of almost all great comic books and we might find something startling similar: the roots of today’s superheroes lie in a particular Jewish culture transplanted from Europe to the United States in the first half of the 20th-century. The creators of Superman, Batman, Captain America, Spider-Man, Incredible Hulk, Fantastic Four, X-Men and many others were all from Jewish families and, as some have argued, infused their characters with Jewish values. Jack Kirby, hailed as the "King of Comics" and creator of many pen-and-ink superheroes, once said that "Underneath all the sophistication of modern comics, all the twists and psychological drama, good triumphs over evil. Those are the things I learned from my parents and from the Bible. It’s part of my Jewish heritage."

Yet, names were changed for the sake of assimilation: Kirby was born as Jacob Kurtzberg; Stanley Lieber, creator of Spider-Man, became Stan Lee; Robert Kahn, creator of Batman, became Bob Kane, and so forth. And explicit religious references were generally disregarded. The Thing’s 2002 revelation charts in microcosm some of the changes that have taken place in the four decades after his inception. Partly this is a shift in the specifics of Jewish identity in the wake of the Nazi takeover of much of Europe mid-century. But the fact that religious references in general have become more accepted in comics of the past decade or so tells us a good deal about the 21st century’s connection between pop culture and religion.

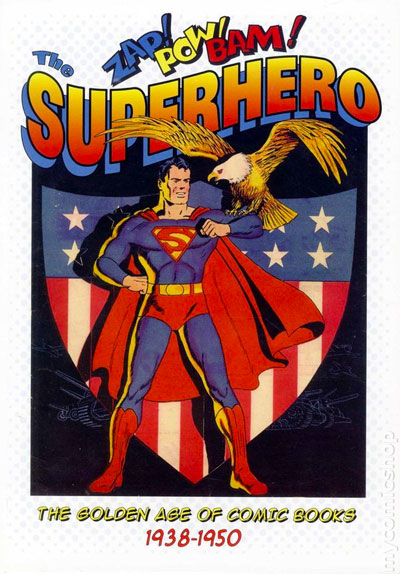

Almost as if fulfilling the dying man’s words ("you can always ... get them back") a number of books and museum exhibitions have emerged in recent years charting a clear line between the rise of comics and something about the Jewish identities of the young artists who created them. I recently visited the exhibition, bulkily titled "Zap! Pow! Bam! The Superhero: The Golden Age of Comic Books, 1938-1950," at Baltimore’s Jewish Museum of Maryland. The late Jerry Robinson, who worked with the comic book industry for many years and who created Batman’s sidekick "Robin," set up the exhibition with the William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum in Atlanta in 2004. It has since traveled the United States. The Baltimore version had it confined to one large room, making the already visually complex imagery of comics more scrambled, but the overall effect worked a bit like a page with text and image conjoined in various panels. What the exhibition does well is show the rise of the superhero in comic books, and how that is situated within a specific socio-political-cultural field. This is no comic for comic’s sake.

Refleting The War Around Them

The so-called Golden Age of comics emerges out of the Great Depression and the rise of Hitler and Japanese militarism. From 1940 to 1945, comic book sales tripled. Centered especially around New York, a number of young Jewish artists began to create superheroes in the midst of social fragmentation and uncertainty. The creation story occurs when Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster wrote and inked Superman as the first issue of Action Comics in June 1938. The next year Bill Finger and Bob Kane published the first appearance of Batman in the series Detective Comics. They were all in their early-mid 20s.

Mythical ties were made implicit: Superman was like Moses, saved from destruction as an infant and sent off to liberate a people. The magic word SHAZAM!, shouted by Billy Batson/Captain Marvel is an acronym of the names Solomon, Hercules, Atlas, Zeus, Achilles, and Mercury, though that is apparently an insider’s secret knowledge. And Wonder Woman, for those who looked deeper, came from Paradise Island, among a people devoted to Aphrodite. Beyond the specific, sometimes esoteric connections known only to fanboys and other initiates, there is the longstanding myth of the hero’s journey, on which these characters are also based. Heroes have typically been human, and just that. So the need for something more, something super, at this time and place is curious.

Quentin Tarantino’s revenge fantasy in "Inglourious Basterds" was nothing new. Comics of the 1940s have Superman, Captain America, Captain Marvel and several others facing down the Nazis, destroying their weapons of war and punching Hitler in the face. And it is the Nazi aggression that spurred many of the superheroes through the Golden Age. While I’m not totally convinced of the connection, Jane Leavey, Director of the Breman Museum writes in the forward to the "Zap! Pow! Bam!" catalog that the superheroes took on the role of tikkun olam, the repairing of the world imbedded in some elements of Jewish tradition. Certainly Batman is doing justice (at least the 1939 Batman was) and fixing what’s not right, but it’s not clear that this is altogether the same thing as that Hebrew phrase connotes. Regardless, with the comic book, as in real life, religion is in the action.

Beyond Good and Evil in the New Normal

Once the war was over, economic prosperity rose, and America emerged into a new normal as world superpower, the need for the superhero began to diminish. One wall text in the exhibition laments, "The ‘common man,’ once so in need of a superhero to protect and defend him against urban corruption and the forces of evil, was now living comfortably in a middle-class American suburb."

In the midst of the cultural turmoil, and legitimate fears at the time of the Second World War, the images and narratives of comic books provided clear cut differences between the good guys and bad guys. Sometimes the bad guys were inventions of the artists’ studios, sometimes they were based on reality. Regardless, you knew who was who. See here the depiction of the Joker from the 1940s, created by Jerry Robinson.